FIRST SECTION

CASE OF NOVAYA GAZETA V VORONEZHE v. RUSSIA

(Application no. 27570/03)

JUDGMENT

STRASBOURG

21 December 2010

FINAL

20/06/2011

This judgment has become final under Article 44 § 2 (c) of the Convention. It may be subject to editorial revision.

In the case of Novaya Gazeta v Voronezhe v. Russia,

The European Court of Human Rights (First Section), sitting as a Chamber composed of:

Christos Rozakis, President,

Nina Vajić,

Anatoly Kovler,

Elisabeth Steiner,

Khanlar Hajiyev,

Giorgio Malinverni,

George Nicolaou, judges,

and Søren Nielsen, Section Registrar,

Having deliberated in private on 2 December 2010,

Delivers the following judgment, which was adopted on that date:

PROCEDURE

1. The case originated in an application (no. 27570/03) against the Russian Federation lodged with the Court under Article 34 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (“the Convention”) by the Editorial Board of the Novaya Gazeta v Voronezhe newspaper, a limited liability company under Russian law registered in Voronezh (“the applicant”), on 26 July 2003.

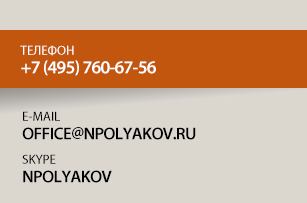

2. The applicant was represented by Ms M.A. Ledovskikh, a lawyer practising in Voronezh. The Russian Government (“the Government”) were represented Mr P. Laptev, former Representative of the Russian Federation at the European Court of Human Rights.

3. On 26 May 2005 the President of the First Section decided to give notice of the application to the Government. It was also decided to examine the merits of the application at the same time as its admissibility (Article 29 § 1).

THE FACTS

I. THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF THE CASE

A. The impugned article and the defamation claims

4. On 2 April 2002 the Novaya Gazeta v Voronezhe newspaper (“the newspaper”) published an article by Mr E.P. entitled “Atomic Mayor” («Атомный мэр»). The article concerned abuses and irregularities allegedly committed by Mr S., the mayor of Novovoronezh, and by other municipal officials, including Mr B., a deputy head of administration and director of the economy and finance department, and Mr P., the chairman of the education committee. The article also mentioned certain private parties who supplied goods or performed services for the municipal authorities, including Mr F., a local businessman who did renovation work for State-funded institutions.

5. The article quoted extensively from the Report on the Composite Audit of the Novovoronezh Town Administration, carried out by the Audit Department of the Ministry of Finance for the Voronezh Region from 13 November to 27 December 2001 (“the audit report”).

6. On 8 May 2002 Mr S., Mr B., Mr P. and Mr F. lodged an action for defamation against the applicant. They claimed that the following extracts from the article were untrue and damaging to their reputation:

“… In autumn 2001 a group of campaigners in Novovoronezh collected signatures for a vote of no confidence in Vladimir S. They collected nearly three thousand signatures …” [paragraph 4]

“… For a long time the Novovoronezh town administration failed to transfer payments to the compulsory medical insurance fund. In the mayor’s opinion, these transfers were not mandatory, but a commercial court decided otherwise. Thanks to S., in 2002 the town budget will lose a further twenty million [roubles] …” [21]

“… Mayor S. still adheres to the ideas of Socialism and Communism; not only once did he enter the ranks of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation … occasionally he left its ranks …” [23]

“… [In addition to the budget, Novovoronezh has an off-budget fund. And a substantial one.] One would only wonder at the way the mayor and his faithful companion, comrade B., the head of the economy and finance department doubling as executive director of all funds, handled its assets …

Thus, thanks to the efforts of two prominent economists, the town lost an amount comparable to nearly one half of the annual budget …” [34, 47]

“The chairman of the education committee of the Novovoronezh administration, Mr P., did not produce any documents showing that these students came from needy or large families as he claimed …”

What kind of needy families were these if even Mr P., the chairman of the education committee, does not know them?” [57, 58]

“Inquisitive readers would ask: why did Mr B. care so much about the military unit in the village of Boevo and the regional psychiatric hospital (let’s recall the charitable contribution of 300,000 roubles made to the hospital)? And they would start looking for an answer.

Is it not in military unit no. 51205 that the son of the aforementioned official is doing his military service?

Is it not in the regional psychiatric hospital that a relation or a namesake of Mr B. has just undergone a medical examination in order to escape punishment for a serious criminal offence? … [67-69]

And what about the honest Mayor S.? He does not know, perhaps, about the tricks of his deputy?

On the contrary. He does know and he even personally signs payment orders for the transfer of money to the State enterprise ‘Voronezh regional clinical psychiatric hospital’…” [71, 72]

“The thing is that the notion of competitions (tenders) for the provision of services for State-funded organisations ceased to exist in the town long ago. If our fair and Communist-minded mayor S. liked Mr P. (they have done much business together), he could have as much work as he liked. He could supply computers at 150,000 roubles a piece and feed children in kindergartens at inflated prices …” [87]

“… During the audit an estimate of the repair work actually performed in the town stadium was made up. The cost of the actual work done amounted to nearly 500,000 roubles. So, Mr S. and Mr F., where have the remaining 1,300,000 roubles gone? …” [93]

B. The first-instance proceedings

7. On 10 and 11 September 2002 the Sovetskiy District Court of Voronezh (“the trial court”) took evidence from the parties. The plaintiffs produced judgments of commercial courts pursuant to which the amount of 26,927 Russian roubles (RUB) had been recovered from the Novovoronezh municipal authorities in respect of payments to the medical insurance funds. Mr S. also produced a document showing that he had been a member of the Communist Party since 1995 and never relinquished his membership.

8. The applicant had at its disposal ordinary copies of the audit report and the report of 22 November 2001 on the verification of the work done at the stadium and shooting gallery (“the stadium report”). Since ordinary copies, as opposed to certified copies, had no evidentiary value, the applicant asked the trial court to obtain the originals. The trial court refused the request because the applicant had not shown that it had attempted to obtain the originals itself.

9. Throughout October 2002 the applicant unsuccessfully sought to obtain the originals from the Audit Department of the Ministry of Finance for the Voronezh Region, the town department of the interior and the Voronezh Regional and Novovoronezh Town Prosecutors’ Offices.

10. The applicant renewed its request for a court injunction requiring the relevant authorities to submit the original documents.

11. On 30 October 2002 the trial court refused the request, without citing any reasons in the text of the judgment. Mr S. withdrew his claim in the part concerning paragraph 4 of the article.

12. On the same day the trial court issued its judgment. It found that all the extracts contested by the plaintiffs had been untrue and damaging to their reputation. The trial court premised its findings on the following principles:

“In such cases, pursuant to Article 152 of the Russian Civil Code, the defendant shall prove the truthfulness of the information disseminated, whilst the plaintiff is only required to show that the defendant disseminated the information. Not only assertions, but also conjectures shall be amenable to proof. Damaging conjectures which are shown to have been unfounded in a court hearing will give rise to an apology. Reliance on rumours, hearsay, opinions of anonymous experts, competent sources, etc. as the basis for the damaging information shall not relieve the defendant from the obligation to show its truthfulness…”

13. The trial court decided that paragraphs 93 and 94 of the article implied the embezzlement of funds by Mr S. and Mr F. However, it noted that the audit report assessed the total cost of work at RUB 1,850,000 and that the defendants failed to adduce any proof of embezzlement.

14. The trial court accepted Mr S.’s opinion that statements in paragraphs 21, 23, 47, 71, 72 and 87 of the article impaired his honour, dignity and reputation. In the trial court’s view, it was incorrect to say that the town “would lose a further 20 million thanks to the mayor” because the payments had been mandatory anyway and, after they had been withheld for some time, a court had ordered their recovery in the same amount. The information on Mr S.’s “discontinuous” party membership was considered untrue because he showed that he had joined the Communist Party once and had not relinquished his membership ever since. The trial court held that in paragraph 47 the author wrongly blamed Mr S. and Mr B. for stopping the funding, because the structure of off-budget funds was regulated by federal government decision. Lastly, as to paragraph 87, the trial court determined that it conveyed an impression that dishonest men, acting under the mayor’s patronage, had made a profit out of kindergartens, but the authors did not produce any evidence showing the truthfulness of that allegation.

15. As regards Mr B., the trial court held that paragraphs 34, 47 and 67-69 of the article were untrue and damaging for his reputation because the defendants failed to prove that Mr B. had been the executive director of “all funds”, that a relation of his, especially a criminal, had been in hiding in the psychiatric hospital or had been treated there, and that he and Mr S. had misspent the town’s budget.

16. The trial court accepted Mr P.’s view that the allegations of abuses in the selection of students and his personal involvement in them (paragraphs 57 and 58) had been insulting for him.

17. The judgment stated:

“Thus, the court has concluded that the plaintiffs’ claims are well-founded because the author and the editors tolerated the publication of an article that contained insulting and untrue statements… without bothering to check all the relevant facts. In accordance with the law… evidence should have been collected before the information was published and it is inappropriate to start collecting evidence after the article was published… Moreover, the plaintiffs have produced before the court a reply from the Novovoronezh prosecutor’s office and a decision of the Novovoronezh police department refusing criminal prosecution in connection with the audit of certain financial matters in the education committee of Novovoronezh in 2000-2001.”

18. The trial court ordered the applicant to pay RUB 10,000 to Mr S., as well as RUB 5,000 to Mr B., Mr P. and Mr F., respectively, that is, RUB 25,000 in total, and also to publish an apology.

C. The appeal proceedings

19. On 8 January 2003 the applicant filed a detailed appeal statement, claiming that the article had concerned an issue of public interest and that the plaintiffs, being “public figures” and State servants, should have been more tolerant to criticism than ordinary citizens. The article was largely founded on the audit report and the district court did not afford the applicant an opportunity to prove the truthfulness of any statements of fact as it refused their request to obtain original documents. Moreover, the trial court ordered the applicant to refute value judgments. The appeal statement read, in so far as relevant, as follows:

“As regards the first document […], [the trial court] referred to the fact that there was no need to request it because the case file contained a decision by the senior police officer of the Novovoronezh GOVD [main department of the interior] to institute a criminal investigation into the facts mentioned in the report by the KRU [the Audit Department].

As regards the second document […], the [trial] court referred to the fact that [it had been stated] in the reply by the Novovoronezh GOVD to the editorial board’s request to provide the document that the GOVD did not have the document in question as it had been forwarded to the Novovoronezh prosecutor’s office, and that there was therefore no need to request it from the GOVD.”

20. On 6 February 2003 the Voronezh Regional Court upheld the judgment of 30 October 2002. It held that the applicant’s arguments that the article had contained value judgments rather than statements of fact was “unsubstantiated”. The court reasoned, in so far as relevant, as follows:

“The dissemination of the information that the plaintiffs seek to refute was proven before the [trial] court and has not been disputed by the respondent. Accordingly the newspaper was obliged to submit evidence before the [trial] court to prove the truthfulness of the information in question.

However, no such evidence was presented before the [trial] court.”

D. Ensuing events

21. On 20 June 2003 the applicant transferred RUB 25,000 to the bank account of the bailiffs’ service in execution of the judgment of 30 October 2002.

22. The applicant published an apology in the 11 – 17 July 2003 issue of the newspaper retracting the information contained in the article.

II. RELEVANT DOMESTIC LAW AND PRACTICE

23. Article 29 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation guarantees freedom of ideas and expression, as well as freedom of mass media.

24. Article 152 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation of 30 November 1994 provides that an individual may seize a court with a request for the rectification of information (сведения) damaging his or her honour, dignity or professional reputation unless the person who disseminated such information proves its accuracy. The individual may also claim compensation for losses and non-pecuniary damage sustained as a result of the dissemination of such information. The rules governing the protection of the professional reputation of a physical person are likewise applicable to the protection of the professional reputation of legal entities.

25. Resolution no. 11 of the Plenary Supreme Court of the Russian Federation of 18 August 1992, as amended on 25 April 1995 (in force at the material time) provided in its Article 2 that to be considered damaging the information (сведения) had to be untrue and contain statements about an individual’s or a legal entity’s breach of the laws or moral principles (commission of a dishonest act, improper behaviour at the workplace or in everyday life, etc.). Dissemination of information was understood as the publication of information or its broadcasting, its inclusion in professional references, public addresses, applications to State officials, as well as its communication in other forms, including orally, to at least one other person. Article 7 of the Resolution governed the distribution of the burden of proof in defamation cases. The plaintiff was to show that the information in question had been disseminated by the defendant. The defendant was to prove that the disseminated information was true and accurate.

THE LAW

I. ALLEGED VIOLATION OF ARTICLE 10 OF THE CONVENTION

26. The applicant complained under Article 10 of the Convention about the interference with its right to freedom of expression, which it alleged was not necessary in a democratic society. Article 10, in so far as relevant, reads as follows:

“1. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers.

2. The exercise of these freedoms, since it carries with it duties and responsibilities, may be subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others, for preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, or for maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary.”

A. The parties’ submissions

1. The Government

27. The Government contested the applicant’s arguments. They claimed that the disputed statements had been statements of fact and not value judgments. The domestic courts had independently assessed the evidence before them and decided on its relevance. The trial court had had before it various pieces of evidence submitted by the parties and had been able to decide on the civil dispute on the basis of evidence it considered sufficient, without using other evidence.

28. The trial court’s refusal to request originals of the audit and stadium reports had been well-reasoned. The applicant had been duly notified of such reasons. The applicant could have complained to a court about the prosecutor’s office’s failure to provide the originals of the documents, but had not done so. Moreover, if the trial court had not included reference to those reasons in the trial minutes, the applicant could have requested modification of the minutes under the relevant domestic laws.

29. The trial court’s judgment of 30 September 2002 had been based on Article 152 of the Russian Civil Code since the applicant had failed to prove the veracity of the statements made in the article. The interference with the applicant’s freedom of expression had pursued a legitimate aim, namely to protect the rights of others, and had been necessary in a democratic society because the article had suggested that the plaintiffs had committed illegal acts. The Government concluded that there had been no violation of Article 10 of the Convention.

2. The applicant

30. The applicant submitted that the disputed statements had been supported by the stadium and audit reports. However, it had been impossible to use the reports as evidence because the author of the article had had only ordinary copies, not originals or certified copies. The domestic courts’ refusal to request the originals or at least certified copies of the reports had had a chilling effect on journalists in possession of ordinary copies of official documents capable of disclosing a matter of public interest. The refusal to open criminal proceedings concerning the facts described in the reports could not, in itself, render the information contained in them false. Moreover, the requirement to prove a value judgment was not compatible with freedom of expression.

31. In the appeal statement the applicant’s counsel had referred to the reasoning behind the trial court’s decision not to request certified copies of the documents that had been communicated to her via unofficial channels; the trial minutes had contained no reference to the trial court’s reasoning in that connection.

B. The Court’s assessment

1. Admissibility

32. The Court notes that the application is not manifestly ill-founded within the meaning of Article 35 § 3 of the Convention. It further notes that it is not inadmissible on any other grounds. It must therefore be declared admissible.

2. Merits

(a) General principles

33. The Court reiterates at the outset that freedom of expression constitutes one of the essential foundations of a democratic society; subject to Article 10 § 2, it is applicable not only to “information” or “ideas” that are favourably received or regarded as inoffensive or as a matter of indifference, but also to those that offend, shock or disturb. Freedom of expression is subject to a number of exceptions which, however, must be narrowly interpreted and the necessity for any restrictions must be established convincingly (see The Sunday Times v. the United Kingdom (no. 2), 26 November 1991, § 50, Series A no. 217).

34. The test of “necessity in a democratic society” requires the Court to determine whether the “interference” complained of corresponded to a “pressing social need”, whether it was proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued and whether the reasons given by the national authorities to justify it are relevant and sufficient (see The Sunday Times v. the United Kingdom (no. 1), 26 April 1979, § 62, Series A no. 30). In assessing whether such a “need” exists and what measures should be adopted to deal with it, the national authorities are left a certain margin of appreciation. This power of appreciation is not, however, unlimited but goes hand in hand with a European supervision by the Court, whose task it is to give a final ruling on whether a restriction is reconcilable with freedom of expression as protected by Article 10 (see Nilsen and Johnsen v. Norway [GC], no. 23118/93, § 43, ECHR 1999-VIII, and Jerusalem v. Austria, no. 26958/95, § 33, ECHR 2001-II).

35. The press plays an essential role in a democratic society. Although it must not overstep certain bounds, in particular in respect of the reputation and rights of others, its duty is nevertheless to impart – in a manner consistent with its obligations and responsibilities – information and ideas on all matters of public interest (see De Haes and Gijsels v. Belgium, 24 February 1997, § 37, Reports of Judgments and Decisions 1997-I). Not only does it have the task of imparting such information and ideas, the public also has a right to receive them. Were it otherwise, the press would be unable to play its vital role of “public watchdog” (see Thorgeir Thorgeirson v. Iceland, 25 June 1992, § 63, Series A no. 239, and Bladet Tromsø and Stensaas v. Norway [GC], no. 21980/93, § 62, ECHR 1999-III).

36. Article 10 protects not only the substance of the ideas and information expressed, but also the form in which they are conveyed (see Oberschlick v. Austria (no. 1), 23 May 1991, § 57, Series A no. 204). Journalistic freedom also covers possible recourse to a degree of exaggeration, or even provocation (see Prager and Oberschlick v. Austria (no. 1), 26 April 1995, § 38, Series A no. 313).

37. In its practice, the Court has distinguished between statements of fact and value judgments. While the existence of facts can be demonstrated, the truth of value judgments is not susceptible of proof. The requirement to prove the truth of a value judgment is impossible to fulfil and infringes freedom of opinion itself, which is a fundamental part of the right secured by Article 10 (see Lingens v. Austria, 8 July 1986, § 46, Series A no. 103).

38. However, even where a statement amounts to a value judgment, the proportionality of an interference may depend on whether there exists a sufficient factual basis for the impugned statement, since even a value judgment without any factual basis to support it may be excessive (see Jerusalem, cited above, § 43).

(b) Application of the above principles to the present case

39. The Court observes that it was not disputed between the parties that the civil proceedings for defamation against the applicant constituted an interference with its freedom of expression and that this interference was in accordance with the law and pursued the legitimate aim of protecting the plaintiffs’ reputation. It remains to be determined whether this interference was “necessary in a democratic society”.

40. The Court reiterates that its task in exercising its supervisory function is not to take the place of the national authorities but rather to review under Article 10, in the light of the case as a whole, the decisions they have taken pursuant to their power of appreciation (see Fressoz and Roire v. France [GC], no. 29183/95, § 45, ECHR 1999-I, and Egeland and Hanseid v. Norway, no. 34438/04, § 50, 16 April 2009).

41. In examining the particular circumstances of the case, the Court will take the following elements into account: the position of the applicant, the position of the plaintiffs who instituted the defamation proceedings, and the subject matter of the debate before the domestic courts (see, mutatis mutandis, Jerusalem, cited above, § 35).

42. As regards the applicant’s position, the Court observes that the applicant was sued in its capacity as the editorial board of the newspaper. In that connection it points out that the most careful scrutiny on the part of the Court is called for when, as in the present case, the measures taken or sanctions imposed by the national authority are capable of discouraging the participation of the press in debates over matters of legitimate public concern (see Jersild v. Denmark, 23 September 1994, § 35, Series A no. 298).

43. Turning to the respective positions of the plaintiffs who brought civil proceedings against the applicant, the Court notes the following.

44. Mr S. was the elected mayor of Novovoronezh. The Court reiterates that a politician acting in his public capacity inevitably and knowingly lays himself open to close scrutiny of his every word and deed by both journalists and the public at large (see, among other authorities, Colombani and Others v. France, no. 51279/99, § 56, ECHR 2002-V).

45. Mr B. and Mr P. were civil servants employed by the municipal authorities. The Court notes that civil servants acting in an official capacity are, similarly to politicians albeit not to the same extent, subject to wider limits of acceptable criticism than a private individual (see, mutatis mutandis, Janowski v. Poland [GC], no. 25716/94, § 33, ECHR 1999-I).

46. Mr F., for his part, was a contractor performing renovation work in State-funded institutions and thus a recipient of public funds. The Court points out that private individuals lay themselves open to scrutiny when they enter the public arena and considers that the issue of the proper use of public funds is undoubtedly a matter for open public discussion.

47. The Court accordingly concludes that all four plaintiffs being to a certain extent exposed to public scrutiny as regards their professional activities ought to have shown a greater degree of tolerance to criticism in a public debate on a matter of general interest than a private individual (see, mutatis mutandis, Lingens, cited above, § 42).

48. Turning to the subject matter of the debate before the domestic courts, the Court notes that the impugned article mainly contained information about the management of public funds by the mayor and the civil servants (see paragraph 6 above). This was indisputably a matter of general interest to the local community which the applicant was entitled to bring to the public’s attention and which the local population were entitled to receive information about (see, mutatis mutandis, Cumpǎnǎ and Mazǎre v. Romania [GC], no. 33348/96, §§ 94 – 95, ECHR 2004-XI). The Court reiterates in this respect that there is little scope under Article 10 § 2 of the Convention for restrictions on political speech or on debate on questions of public interest (see Feldek v. Slovakia, no. 29032/95, § 74, ECHR 2001-VIII).

49. The Court will further consider the newspaper article as a whole and have particular regard to the words used in its disputed parts and the context in which they were published, as well as the manner in which it was prepared (see Sürek v. Turkey (no. 1) [GC], no. 26682/95, § 62, ECHR 1999-IV, and Tønsbergs Blad A.S. and Haukom v. Norway, no. 510/04, § 90, ECHR 2007-III).

50. The Court points out at the outset that the impugned assertion concerning Mr S.’s alleged discontinued membership of the Communist Party (paragraph 23 of the article) was a factual statement, not a value judgment. However, it is not persuaded that such a statement could be capable of damaging Mr S.’s reputation given that neither adherence to the Communist Party nor resigning from it constituted an offence under Russian law at the material time.

51. The Court further considers that the remainder of the impugned statements mostly reflected the journalist’s perception of the situation concerning the distribution of the town’s off-budget funds. Certain expressions used by Mr E.P. could be considered harsh and provocative, but not to the extent of overstepping the permissible degree of exaggeration. The purpose of publishing the article was to call for closer public and independent control over the spending of off-budget funds in order to prevent or stop possible corrupt practices by the local officials. The Court considers therefore that the impugned statements in the present case reflected comments on matters of public interest and are thus to be regarded as value judgments rather than statements of fact.

52. However, in the present case the domestic courts considered all the contested extracts to have been statements of fact, without examining whether they could be considered to be value judgments (see paragraphs 12 and 20 above). Their failure to embark on that analysis was accounted for by the position of the Russian law on defamation at the material time, which, as the Court has already found, made no distinction between value judgments and statements of fact, referring uniformly to “statements” («сведения»), and proceeded from the assumption that any such “statement” was amenable to proof in civil proceedings (see Grinberg v. Russia, no. 23472/03, § 29, 21 July 2005, and Zakharov v. Russia, no. 14881/03, § 29, 5 October 2006).

53. The Court also reiterates that, even where a statement amounts to a value judgment, the proportionality of an interference may depend on whether there exists a sufficient factual basis for the impugned statement, since even a value judgment without any factual basis to support it may be excessive (see De Haes and Gijsels, cited above, § 47, and Oberschlick v. Austria (no. 2), 1 July 1997, § 33, Reports 1997-IV).

54. In the present case Mr E.P. relied on the audit report issued by a governmental agency (see paragraph 5 above). In the Court’s view the fact that the journalist had no access to the original or a certified copy of the report does not deprive the text in his possession of its informative value (see Bladet Tromsø and Stensaas, cited above, § 68). It follows that the report in question may have contained prima facie evidence that the value judgment expressed in the article published by the applicant was fair comment (see Jerusalem, cited above, § 45).

55. The Court points out that the domestic courts refused to take any steps to obtain an original or a certified copy of either the audit or the stadium reports. Moreover, it is struck by the fact that neither the trial nor the appeal courts tried to assess whether the information presented in the article had any factual basis, or even mentioned that Mr E.P. had referred to two official documents to support his allegations.

56. It is impossible to state what the outcome of the proceedings would have been had the trial court taken steps to obtain the evidence which the applicant sought to adduce; but the Court attaches decisive importance to the fact that it refused to obtain such evidence, judging it irrelevant (see, mutatis mutandis, Castells v. Spain, 23 April 1992, § 48, Series A no. 236). It considers that, in requiring the applicant to prove the truth of the statements made in the article while at the same time depriving it of an effective opportunity to adduce evidence to support those statements and thereby show that they constituted fair comment, the domestic courts overstepped their margin of appreciation (see Jerusalem, cited above, § 46).

57. The Government argued that the information contained in the disputed article had in fact suggested that the plaintiffs had committed crimes and there was thus a pressing social need to protect the plaintiffs and to prevent the careless use of such serious allegations. The Court can accept this argument in principle as it has repeatedly attached particular importance to the duties and responsibilities of those who avail themselves of their right to freedom of expression, and in particular, of journalists (see Jersild, cited above, § 31, and Prager and Oberschlick, cited above, § 37). However, in the circumstances of the present case the Court finds no indication of such deliberate carelessness on the part of the applicant. It rather appears that Mr E.P.’s statements did not constitute a gratuitous personal attack as they were made in a particular political situation in which they contributed to a discussion on a subject of general interest such as the use made of budgetary funds (see, mutatis mutandis, Unabhängige Initiative Informationsvielfalt v. Austria, no. 28525/95, § 43, ECHR 2002-I).

58. It is noteworthy in this connection that the district court adopted an unusually high standard of proof and determined that, as the criminal proceedings in connection with financial irregularities were not pursued, the information provided in the impugned article lacked a sufficient factual basis (see paragraph 17 above). The Court reiterates in this respect that the degree of precision for establishing the well-foundedness of a criminal charge by a competent court can hardly be compared to that which ought to be observed by a journalist when expressing his opinion on a matter of public concern, in particular when expressing his opinion in the form of a value judgment (see Unabhängige Initiative Informationsvielfalt, cited above, § 46). The standards applied when assessing a public official’s activities in terms of morality are different from those required for establishing an offence under criminal law (see Scharsach and News Verlagsgesellschaft v. Austria, no. 39394/98, § 43, ECHR 2003-XI). Therefore, the Court is reluctant to follow the logic implied in the district court’s reasoning that in the absence of criminal prosecution of the plaintiffs no media could have published an article linking them to instances of alleged misuse of public funds without running the risk of being successfully sued for defamation.

59. In conclusion, the Court finds that the standards applied by the Russian courts were not compatible with the principles embodied in Article 10 and that the courts did not adduce “sufficient” reasons to justify the interference in issue, namely the imposition of a fine on the applicant for having published the impugned article. Therefore, having regard to the fact that there is little scope under Article 10 § 2 of the Convention for restrictions on debate on questions of public interest (see, among other authorities, Sürek, cited above, § 61, and Guja v. Moldova [GC], no. 14277/04, § 74, ECHR 2008-…), the Court finds that the domestic courts overstepped the narrow margin of appreciation afforded to Member States, and that the interference was disproportionate to the aim pursued and was thus not “necessary in a democratic society”.

60. Accordingly, there has been a violation of Article 10 of the Convention.

II. APPLICATION OF ARTICLE 41 OF THE CONVENTION

61. Article 41 of the Convention provides:

“If the Court finds that there has been a violation of the Convention or the Protocols thereto, and if the internal law of the High Contracting Party concerned allows only partial reparation to be made, the Court shall, if necessary, afford just satisfaction to the injured party.”

A. Damage

62. In its just satisfaction claims of 16 November 2005 the applicant claimed 882 euros (EUR) in respect of pecuniary damage – the equivalent of the sum in Russian roubles that it had paid to the plaintiffs plus inflation. It provided a copy of the bank transfer order to the bailiffs’ service dated 20 June 2003 for the amount of 25,000 Russian roubles (RUB) (the equivalent of EUR 866 at the official exchange rate established by the Central Bank of Russia on 16 November 2005).

63. The Government stated that there was no evidence that the applicant had actually paid the sum in question.

64. The Court points out that the applicant provided documentary evidence that it had in fact paid the judicial award and awards the applicant EUR 866 in respect of pecuniary damage. The applicant did not present other claims.

B. Default interest

65. The Court considers it appropriate that the default interest should be based on the marginal lending rate of the European Central Bank, to which should be added three percentage points.

FOR THESE REASONS, THE COURT UNANIMOUSLY

1. Declares the application admissible;

2. Holds that there has been a violation of Article 10 of the Convention;

3. Holds

(a) that the respondent State is to pay the applicant, within three months from the date on which the judgment becomes final in accordance with Article 44 § 2 of the Convention, EUR 866 (eight hundred and sixty-six euros), plus any tax that may be chargeable, in respect of pecuniary damage, to be converted into Russian roubles at the rate applicable at the date of settlement;

(b) that from the expiry of the above-mentioned three months until settlement simple interest shall be payable on the above amount at a rate equal to the marginal lending rate of the European Central Bank during the default period plus three percentage points;

4. Dismisses the remainder of the applicant’s claim for just satisfaction.

Done in English, and notified in writing on 21 December 2010, pursuant to Rule 77 §§ 2 and 3 of the Rules of Court.

Søren Nielsen Christos Rozakis

Registrar President

NOVAYA GAZETA V VORONEZHE v. RUSSIA JUDGMENT